Not everyone has a national monument in their back yard…

I’ve been looking at the history of my house, which is a small cottage, built in 1872, a few minutes’ walk from the city centre. In the tiny back yard there is a section of the Roman wall, clearly visible and about a metre high (with a much later, inter-war red brick wall built on top of it, to raise the height of what is, in effect, a boundary wall between properties).

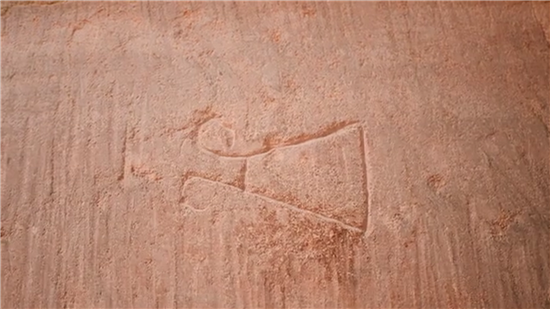

I didn’t know it was there, when I bought the house, until one of my neighbours (a local history buff) told me about it. It is now exposed – I’ve had it repointed (nominally, each house is responsible for the maintenance of “their” section of wall), and I’ve had the horrid white masonry paint stripped off, revealing the wall in all its nearly 2,000 year glory. On one large, locally quarried stone there is the stonemason’s mark, hammered in – a sort of roundel, with the faint image of a head embossed in it. The builders told me they had seen things like this before, and said it was the stonemason’s way of leaving his “signature” on his work. I have even had requests from local historians to come and see it!

My cottage is one of a pair, built at the same time by a speculative builder who acquired the land and seemed to want to make as much money from his tenants as possible – hence 2 small cottages, 2-up, 2-down, rather than one larger house. The same family, descendants of the builders, kept the cottages for the next 60 or 70 years, as the source of a regular income for several generations.

The house is in one of the oldest streets in Gloucester, which was known as Green Dragon Lane in medieval times (in fact, right up to the English Civil War, when the street name was changed). Apparently, there was a black and white timbered pub at one end of the street, called the Green Dragon. Not very far away are the remains of the old tram lines that once ran from Leckhampton quarry, via London Road, all the way to the Docks in Gloucester. And on one corner of the street was the Georgian built first ever Gloucester Royal Infirmary, erected by funds from public subscription in the 1780’s (now demolished, but still operational within living memory until the last 3 decades or so of the twentieth century).

I’ve looked at the first edition Ordnance Survey maps for my neighbourhood and, in 1880 the cottage was surrounded on the northern elevation by a small orchard. In Edwardian times this became a small municipal park. And in the 1930’s an art deco educational establishment was built on the site (now demolished, but remembered fondly by lots of Gloucester people).

I’ve also looked at the census from 1911, and the 1939 Register, to find out more about the people who then inhabited my house. In 1911, a fruit & vegetable hawker was the head of the household, with his wife (20 years his senior, which was unusual in those days) and their male lodger. The vegetable hawker appears to have sold his wares on or near The Cross. The lodger’s occupation was listed as postman. By 1939, the house was lived in by a retired hod carrier, whose workplace was probably at the Docks, aged at least 80 years old (again, unusual in those days), who had been born well before the house was built.

Few original features were left in the house, when I bought it. Although my new neighbour told me there would have been a coal-fired, black-leaded range in the only parlour, and a scullery where the kitchen and utility room are, probably with some sort of solid fuel enamel cast boiler for washing clothes and sheets, and an outside privy (shared with the cottage next door) in the back yard. There would have been flagstones or, more likely, quarry tiles, on the ground floor, long since ripped out. And I know, from my builders, that the original pine panelled thumb-latch doors are up in the loft space, having been dumped there for convenience during one of the many refurbishments the house has lived through.

There is a community garden round the corner – you have to pay an annual subscription which grants you access – and this is where the troops in the Civil War set up their cannons which bombarded Southgate Street and its environs during the Siege of Gloucester. The 5-storey houses, overlooking the 1.5 acre garden, many painted in pastel tones to their front facades, were built in circa 1820, so they are Regency in style, as townhouses for wealthy Gloucester merchants and sea captains, a stone’s throw from the Docks. Opposite these impressive townhouses is a rather grand church, built about 50 years after the dwellings in the then popular Italianate style, beloved by so many ecclesiastical architects of the period.

There would have been no electricity to the cottage, of course, in its first 35 or 40 years, and initially no mains gas. I recall, as a toddler in the very early 1960’s, visiting my grandmother (born 1883) who relied on wall mounted gas jets in her old house, and refused to have electricity installed because “you don’t know where it comes from, and you don’t know how it works, so I don’t trust it!”

The front of my property – set back from the pavement by 25 feet, and the width of the house – would have probably been rather like a mini-market garden, with evidence of some outbuildings, a coal store, and possibly was a source of some fresh produce for the cottages, but on a very small scale. It is now a gravel drive, for the inevitable car, and a paved courtyard space with shrubs, small trees and a seating area.

The house is now slap bang in the middle of a Local Authority conservation area, with insistence on proper roof slates, and timber casement windows and doors, with many of the cottages painted pretty colours. It would be unrecognisable to the original inhabitants when the cottages were built 150 years ago. And the few shillings a week in rent, in the mid-Victorian times, have now risen to several hundred a month in twenty-first century mortgage repayments!

My interest in house history dates back to the late 1970’s (I was at secondary school), when I became aware of Dan Cruickshanks’ campaign to prevent the historic Huguenot silk weavers’ terraces being demolished in Spitalfields, east London. Today, of course, the subject has been popularised by TV programmes such as A House Through Time, presented by academic and historian, David Olusoga.

I’ve done most of my research online (Ancestry is a rich source of digitised records), as well as talking to neighbours (including an elderly relative of my neighbour, who had lived in the cottage, as a very small boy, in 1930, when it housed something like 6 people!). I’ve also looked at maps, in the collections at Gloucestershire Archives, and had a look at Know Your Place south-west, an online history portal, which is a great source for local historians and archivists.

Every house really does tell a story, and starting out, uncovering the history of your house, is rather like being a detective – you find clues, you have a hunch, you look at the records. It’s great fun, and I’ve barely scratched the surface – what I’ve discovered, to date, has probably taken me no more than a couple of hours of research. I’d like to know more – have any inhabitants of the house had unusual names, or occupations, or have any of them been admitted to the local gaol or asylum? (I discovered this quite by chance about an occupant of a previous Victorian house I lived in). But I don’t have the time, at the moment, which is a pity but is food for thought for the future.

Why not have a go yourself, looking at your own house history? What will you discover about your house, its previous occupants and your neighbourhood? Why not book that appointment to come and talk to us at Gloucestershire Archives? We’d be delighted to see you, and very happy to get you started. It’s true that not everyone has a national monument in their back yard, but it is true that every house is rich in history.

Sally Middleton, Community Heritage Development Manager – Gloucestershire Archives.

To learn more about Stone Mason's marks visit www.gloucesterhistoryfestival.co.uk/signs-of-history/ and watch the short film Signs of History: Introducing Gloucester Cathedral and the Stone Mason's Marks by Olivier Jamin

Stonemason's marks found on the Cathedral pillars.