Volunteering – and Why People Do It

For much of my adult life, I have worked (on and off) as a volunteer. I have experience of volunteering in homeless shelters, at Christmas, in Citizens’ Advice Bureaux, for UNESCO (in the Middle East) and for a non-profit, in New York, providing a range of services to elders in need. I also write numerous articles, for various publications, in a voluntary capacity, on a wide range of topics – equalities, the coronavirus pandemic, project work and a whole number of other subjects.

I suppose I do it for two main reasons – it makes me feel good, and it offers opportunities for learning and for meeting new people. The sort of people I may otherwise never meet. I have not done any hands-on volunteering for some years, because of other priorities and having a busy working life. But it’s something I may well get back to, at some point.

Volunteers are often the unsung heroes of organisations. They bring new ideas, a wealth of experience, energy, commitment and enthusiasm. And they bring their time, that most precious of commodities. Volunteers do not, of course, expect to be paid – that is not why they do it – although out of pocket expenses should always be paid.

I started volunteering when I was a university student; I thought it would be a good thing to do, and something to add to my CV. As a volunteer, I have visited the United Nations, in New York, seen first-hand some of the political and religious strains in the Middle East, met people from all walks of life and seen poverty and illness up close. It has been quite a journey, and I would recommend volunteering to everyone, but especially to young people.

When I went to university, in the late 1970s, I moved to a big, Northern city, from a sleepy market town. The market town is now three times bigger than it was when I was growing up there, and bears very little resemblance to my childhood home. It’s fair to say that life was very sheltered and homogenous – for example, I didn’t have a conversation with, say, a black person, until I went to university. At that time, there was no social media, no internet, and people who were different from those around me were simply not visible – not on the TV, or in newspapers. Volunteering (starting in my late teens) was a way for me to “broaden my horizons” – yes, it’s a bit of a cliché, but also a truism. Young people today do have access to far more information than people of my generation had, but there is nothing that beats getting involved, getting your hands dirty and getting stuck in. Social media platforms, the internet and such like may be effective in making people more aware, but I’m very much an advocate of getting out there and just doing it.

Nothing in the world beats experience, and I was reminded of this recently in conversation with a colleague in another sector, who commented on all the different jobs I’ve done (she was asking me about where I’d worked, as what, and when). Sometimes it’s good to take a step back, and ask yourself “What have I learned from what I’ve done?” And experience is invaluable, whether paid or unpaid, because it gives an authenticity to whatever it is you’re talking about having learned.

I sometimes think back to my time as a volunteer in the Middle East; I was there for a whole summer in 1979, as an undergraduate. I was billeted in a ramshackle single-storey house, in a village in the hills, no glazed windows, no furniture to speak of, just a dirt floor with some large cushions. All my fellow volunteers were men, apart from one other woman, and all of us were from across the globe; we had come together to do a community project in the village. It was hard, physical work. A few months after my extended visit this country descended into civil war, following a military coup. On one occasion, during my stay, I was invited to eat supper with the tribal elders. The women in this multi-generational household didn’t join us, as was the custom in this Muslim country – they sat apart, to eat their food (only after the men had finished theirs, the women had the left-overs). They didn’t speak English, and I didn’t speak their language, so we had to improvise with gestures and body language, and hastily drawn pictures. We sat on the floor, to eat, around a circular dining “table”, a low, revolving metal platter, about 4 feet in diameter. There were no plates or knives and forks – we piled food on to slices of unleavened bread, and ate with our fingers. There was no electricity. There was no TV, no newspapers and transport (limited) was by donkey and cart. There were no shops, just a weekly market about 10 miles away. There were no bathrooms and no plumbing, and no toilets or showers. It was probably less than 2,000 miles away from home, yet a world away in terms of culture. And the food was so different from what I was used to! In many ways, it was an adventure, and one that I’m very glad I had. When I returned home I brought back a small tribal rug, which I’d bartered for in one of the souks, and very many memories which other learning opportunities simply can’t offer.

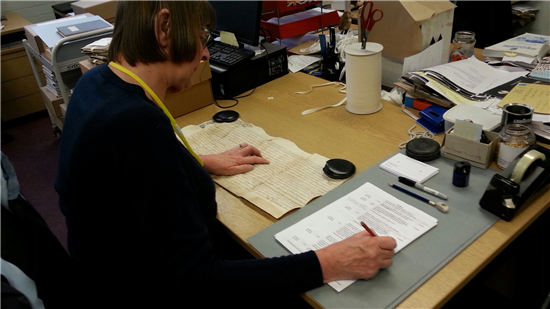

So, that’s my story of how my volunteering journey started. What about yours? People volunteer for all sorts of reasons, and come from all sorts of backgrounds. At Gloucestershire Archives we have dozens of volunteers, all of them connected by a common passion for history. As I said before, people volunteer for all sorts of reasons, and I think one of the principle ones is simply to learn. There are many learning opportunities at Gloucestershire Archives, for volunteers; we have around 20 “job descriptions” for our volunteers. In recent years, we have seen a little more diversity amongst those who volunteer for us, and I think this is a good thing. Above all, we value our volunteers for all the rich life experience they bring, and for the time they so willingly give us. Volunteering is a way of life, for many of our volunteers, and all of us are richer for that.