Mental Health Provision in Gloucestershire – Two Centuries of Institutional Care

The long history of mental health provision in Gloucester starts in 1794, just 5 years after the French Revolution, when a subscription fund was set up to pay for the cost of building what would later become known as Horton Road Hospital in Gloucester (the first County Asylum in Gloucestershire, as it was first known). The subscribers of the day included the vaccinations pioneer, Dr Edward Jenner, from Berkeley in Gloucestershire, Robert Raikes – the founder of Sunday Schools – from Gloucester, and Sir George Onesiphorus Paul, a well-known social reformer and local philanthropist. There is a very fine marble bust of Sir George in Gloucester cathedral.

The Horton Road Asylum did not open until 1823 and several architects were appointed between 1794 and1823. The first architectural drawings, done by William Stark of Glasgow, were inspired by John Nash, responsible for many of the Georgian and Regency crescents and terraces in Bath. The building was designed on the same architectural principles as several gaols of the time. There were inner and outer “Airing Courts”, and these were open-air quads, very much like prison exercise yards, for inmates to “take the air”. In the early days of opening, members of the public were encouraged to come and “view” the lunatics from special observation terraces, and this is something that, today, strikes us as barbaric.

Patients taking the air. Engraved by K H Merz, after W Kaulbach, 1834. Welcome Collection (CC-BY)

Patients taking the air. Engraved by K H Merz, after W Kaulbach, 1834. Welcome Collection (CC-BY)

By the mid 1830’s Horton Road Asylum had the highest rate of recorded cures in the field of mental ill health in all of England. It was the eighth asylum to be built in England, following the success of the Retreat in York, which was largely funded by local Quaker families.

Gloucester has a special significance, in the UK, in the history of mental health. The inaugural meeting of what is now the Royal College of Psychiatrists was held at Horton Road Hospital in Gloucester in 1841. One of the founding members of the Royal College of Psychiatrists was Dr Samuel Hitch, Resident Physician at Horton Road Hospital, and a leading pioneer in the treatment of mental health. He played a major role in creating the Association of Medical Officers of Asylums & Hospitals for the Insane, the forerunner of the now named Royal College of Psychiatrists. For further information please see “Gloucester and the beginnings of the RMPA” in the Journal of Mental Science 449, pp. 603-632, 1961, by A. Walk & DL Walker.

In the same year, 1841, mechanical restraints were withdrawn from the daily routine at Horton Road Asylum. At that time only a handful of asylums had taken this step and it was seen as an enlightened and humane reform. In the 1990’s the main building (a Regency terrace), which was listed, was remodelled as luxury apartments, but I am reliably informed that the subterranean “cells” – along with iron shackles still bolted to the wall – are still intact, under the main access road to the terrace, and were clearly visible during the building works to create the apartments.

By 1883 Gloucester had 3 asylums: the original one, in Horton Road; Barnwood House in Barnwood, and the newly opened Coney Hill Asylum. Horton Road and Coney Hill were both managed by the local authority forerunners of the NHS, with Medical Superintendents being in charge, and Barnwood House was private. With the passing of the Mental Treatment Act 1930, which introduced voluntary patient admissions to asylums, the number of patients grew exponentially. Ivor Gurney, the World War 1 internationally acclaimed poet, was a private patient at Barnwood House. This asylum trialled the introduction of ECT from December 1939, one of the first psychiatric hospitals in Britain to do so, and its medical Directors were interested in experimental psychiatry and treatments that were, at the time, thought of as innovative and forward thinking, including leucotomy. Barnwood House Hospital also introduced psychotherapy for its patients, and was ahead of national trends in doing so.

In 1930 a new Physician Superintendent, Dr Frederick Logan, was appointed to the Coney Hill County Asylum in Gloucester, also known as the Second County Asylum, and he was amongst the first to introduce outpatient care, a dedicated service for adolescents, a form of occupational therapy and “parole” for male patients. He retired in 1955, and saw the changes in the treatment of mental ill health from the introduction of the 1930 Mental Treatment Act (replacing the outdated Lunacy Act 1890) right through to the very early ideas promoting community care, and including the foundation of the NHS in 1948.

Gloucestershire Archives has what is widely regarded as a very comprehensive collection of both clinical and administrative records from 1823 until the last of the County Asylums in Gloucester (Coney Hill Hospital) closed in 1994. An almost complete collection of records outlining treatments, case notes, patient histories, epidemiology, admissions and discharges for well over 170 years.

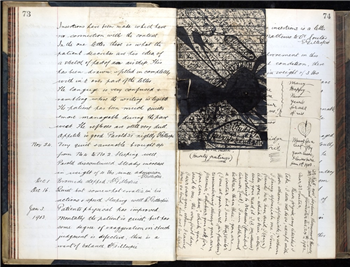

By far the most interesting document held by Gloucestershire Archives, relating to the County Asylums, and Barnwood House, are the patient case notes. These provide wonderful, contemporaneous insights to daily life in the asylums from the time of King George IV (in the 1820’s) right through to Queen Elizabeth II. But, because of data protection laws, you are only allowed to access patient case notes if they are at least 100 years old. There are some exceptions to this, but that is very much the general rule. So for us, today, the vast majority of records we can view relate to the Victorian and Edwardian period.

Barnwood D3725 - Box 31

Barnwood D3725 - Box 31

The patient case notes of this time very often fail to give any sort of medical diagnosis we would recognise today; psychiatry at this time was in its infancy, and there were few or no pharmaceutical treatments for mental illness. Arguably, many conditions were caused by pre-existing physical diseases, poverty, war (there is lots of evidence of cases of “shell shock” from the period 1914-18) and social conditions. Some patients were admitted to the asylum for social, rather than medical, reasons, and could languish in the back wards for decades. A case in point is that of unmarried mothers who were regarded as “fallen women” and admitted to asylums with their illegitimate children as being “morally corrupt” and even a danger to society. Similar cases involved homosexual men, at a time when homosexuality was regarded as aberrant, even morally suspect, and there are several documented cases of these individuals ending up in lunatic asylums. But, of course, a lot of this history is “hidden” because terms like “homosexuality” were rarely, if ever, used.

The same is true in terms of “hidden” or obscure diseases that may have led to “insanity”. A common diagnosis, on admission, was “GPI”, and this is a term you will not find in today’s medical textbooks. GPI was “General Paralysis of the Insane” and referred to the final stages – leading to “madness” and eventual death – of syphilis. Other conditions were often simply referred to as “mania” and there are lots of examples of what we would now call post-natal depression, and even of post-traumatic stress disorder, that were simply, collectively, called “mania”. Today, we know more about mental ill health, most care is provided in the community, there are reliable talking therapies and drugs, there are antibiotics (to treat infections) and we have trained professionals to help and support those living with mental health issues.

If you want to find out more about what lunatic asylums were like, and their day to day routines, a good starting place would be “At Home In The Institution: Material Life in Asylums, Lodging Houses & Schools in Victorian & Edwardian England” by historian and academic Jane Hamlett (pub 2015). We have a copy of this at Gloucestershire Archives. A further, very interesting, source for local family history researchers who want to know more is Ian Hollingsbee’s Gloucester’s Asylums 1794-2002.

Sally Middleton - (Community Heritage Development Manager, Gloucestershire Archives)

sally.middleton@gloucestershire.gov.uk