Reporting our Archaeological Heritage with the Portable Antiquities Scheme

Every year, hundreds of thousands of archaeological items are found by members of the public. On the whole, most items are found by metal detector users but there are still a substantial number found by people walking their dogs or even digging in their back gardens. For instance, one lady found a bronze coin whilst gardening; it was identified as a Follis of the Byzantine Emperor Leo VI (Leo the Wise or Leo the Philosopher) date to 866-912 AD. (See Fig 1).

Fig 1. A copper alloy coin of the Byzantine emperor Leo VI Date: 866-912 AD (database ref GLO-D4B576)

Originally, these coins were dismissed as souvenirs that were brought to Britain over the last two centuries but recent studies of these casual loss finds demonstrates a much more complex story. Some may be regarded as souvenirs but the majority recorded with the Portable Antiquities Scheme were found near the coast in the South Western region of the country. This has led some experts to theorise that these coins, rather than being modern loss, are actually traded items that demonstrate the west of Britain at least continued to have contact to the Eastern Roman Empire long after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Originally, the only mechanism to identify and record these publicly derived archaeological finds was with the help of the museums around the county. However, this service was not only in addition to their core responsibilities, but many did not have the mechanism to help and meant that far fewer than 100 finds could be recorded in a year, far short of the hundreds of thousands that are thought to be found. The solution came about because of a change in the Law of treasure in 1997. The law of treasure is there to insure the most culturally important archaeological finds are protected and stay within the public domain, which will be their local museum, for which the finder and landowner are given a cash reward. However, critics of the original law of Treasure Trove argued that it was vague, ambiguous and not fit for purpose. For example, under Treasure Trove, the gold of Sutton Hoo was not classed as treasure and therefore not protected by law. (Fig 2.)

Fig 2. A 14th century silver seal matrix that shows the Archangel Michael spearing a dragon at his feet and the Virgin Mary holding the infant Jesus to the left this is surrounded by the inscription S': WILL/I: DE: ST/INTES/COMBE which translates as the 'Seal of William of Stintescombe' (Database ref GLO-F457F2). This is treasure under the 1996 Treasure Act but would not be treasure under the old Treasure Trove.

As a result, experts had been lobbying for over a hundred years to come up with something more suitable but it was not until 1997 that Treasure Trove was finally superseded by the 1996 Treasure Act. Under this new law, objects of more than 10% gold or silver that are older than 300 years or groups of coins, again over 300 years old, are classed as treasure, importantly this also includes the finds associated with them as well, see https://finds.org.uk/treasure for more details.

However, treasure does not cover base metal items such as copper alloy (Fig 3) or pottery, stone and flint (Fig 4), all of which account for the vast majority if items that we see.

Fig 3. Fig 4.

Fig 3. An extremely rare Anglo Saxon brooch that dates to the 6th century. These brooches are found in the Kent area, but Gloucestershire in the early 6th century would have been largely under British control, so its discovery could show trade with the Saxons in Kent or an heirloom that was brought with the Saxons as they conquered this area. (Database ref GLO-4E0EBD)

Fig 4. An extremely rare Palaeolithic handaxe that is about half a million years old and is one of the oldest human made artefacts that can be found in the county with only twelve example recorded so far. (Database ref GLO-325A27)

So together with the change in the Treasure Law in 1997, a pilot Portable Antiquities Scheme started with the aim to record all archaeological finds that were not protected but this new law. These humble beginnings saw 6 finds specialists recording objects in key parts of the country and proved to be so successful that it was expanded in 1999 and 2003 so today we now have 37 specialists called Finds Liaison Officers covering the whole of England and Wales, inputting their data on an online database that has nearly 1.5 million recorded objects see https://finds.org.uk/database The recording of these items is voluntary with everything handed back to the finder when we are finished. We assume that this is the only time an archaeologist will see these items so detailed reports are made of each object which can be added to the archaeological record.

By working with the public in this way, we are able to see some amazing finds that give us a glimpse into past lives. Some of these items can be staggering in their own right.

Gloucester Roman dog hoard, this is an assemblage of copper alloy items that are thought to have been looted from a temple of Diana. The most staggering piece of which is a standing hunting dog that is unique to archaeology. (Database ref GLO-BE1187)

The majority are far more modest.

Badly worn Roman coin often referred to as a ‘grot’ for grotty but these humble coins often prove to be the most important archaeological discovery as they have led us to discovery many new archaeological sites. (Database ref GLO-AE25D8)

The recording and mapping of these more humble items can be much more valuable to archaeologists than the gold and silver objects that are protected by the Treasure Act as these simpler items often help us to discover brand new archaeological sites that give us a greater understanding of our past.

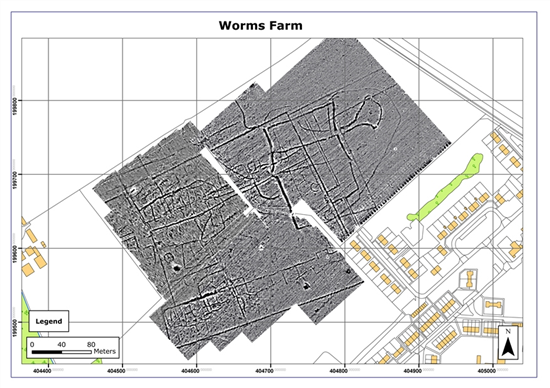

A geophysical survey of a site that shows roman and prehistoric settlement that was discovered as a result of recording poor quality Roman coins nicked named Grots.

Kurt Adams (Gloucestershire County Council Archaeology)